One of my favourite James Shone (see last post) stories involves a pupil called Hot Cross Bun. Whether such a nickname related to his temperament or a fondness for glazed buns containing currants I do not know, but Hot Cross Bun (HCB) stood out because he was supposedly not good at anything. No hint of merit in any subject, not a jot of sporting prowess, no whisper of musical talent, not a speck of a flair in anything whatsoever.

Or so James thought until one day he came upon HCB speaking to another pupil in a corridor; ‘hey X, you were brilliant in that match on Saturday’ he said, causing the recipient to lift his shoulders and beam back in response. The next day James saw HCB with his arm around another fellow pupil. ‘Don’t worry, I’m sure it will work out fine’ he was saying, causing his colleague to nod slowly and break into a smile.

The point James is making, of course, is that HCB’s gift was people; that he had an innate talent for making people feel better about themselves. This is not something that can be easily measured or taught, nor something that is formally celebrated in schools, yet surely it is one of the most precious gifts of all.

Thanks to Harvard Professor of Psychology Daniel Goleman, we have a term for this trait now in common usage: emotional intelligence. As distinct from more traditional measures of intelligence such as IQ (intelligence quotient in case you were wondering), EI essentially refers to the ability of individuals to recognise their own emotions and those of others, and thereby use such information to guide thinking and induce positive behaviour. Goleman also postulated that high levels of EI makes people twice as likely to be successful in their professional careers and enjoy significantly better mental health throughout their lives.

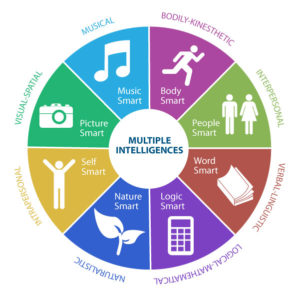

It could be argued that another Harvard Professor (this time of Education), Howard Gardner, got there first in 1983 with the publication of his seminal book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. A standard text amongst aspiring teachers today, Gardner’s book suggests there are many different ways of measuring someone’s intellect, including interpersonal (understanding other’s emotions) and intrapersonal (understanding your own emotions) intelligence. Gardner identified eight specific intelligences:

So what does all this mean for schools?

Firstly, that we should respect the fact that all children are intelligent in their own way and that we shouldn’t be too quick to judge them solely on the basis of formal examinations, performance in which is no guarantee of future success nor lifetime contentment. Finding the things that pupils are really good at is one of the holy grails of teaching.

Secondly, that teachers need to try and tap into such different types of intelligence, all of which closely relate to specific learning styles. This should not force teachers to try and cram every single learning style into every single lesson – something that is nigh-on impossible and that frankly renders lessons ineffectual – though it does mean schools should provide appropriately broad and challenging school curriculums to cater for all different types.

Thirdly, that we should try and develop certain intelligences in pupils, perhaps most vitally the intra- and inter-personal ones. It’s my belief that in schools such intelligences are often far better nurtured outside the classroom via a healthy and diverse range of co-curricular activities that necessitate interaction and collaboration.

I have no idea what Hot Cross Bun is up to today. I would guess, however, that despite his formal school record, he’s living a good life – a happy and successful one which benefits everyone around him. You surely can’t hope for more than that.